Expand all

Collapse all

Purpose

An abdominal assessment is a vast undertaking and the symptoms, often described as gastrointestinal symptoms, are varied. However, it is important to note that there are many differential diagnoses for the gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Common gastrointestinal symptoms |

|

|

Symptom |

Potential body system involvement |

|

Generalised abdominal pain |

All body systems |

|

Flank pain |

Urinary/genital, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, lymphatic |

|

Pelvic pain |

Urinary/genital, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, lymphatic |

|

Anal/rectal pain |

Urinary/genital, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, lymphatic |

|

Epigastric pain |

Gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal |

|

Loss of appetite |

All body systems |

|

Early satiety (feeling full quickly) |

All body systems excepting musculoskeletal |

|

Bleeding either haematemesis or per rectum |

Gastrointestinal system but could be secondary to other disorder of the vascular system. |

|

Bowels not opening |

Gastrointestinal, neurological, urinary/genital |

|

Gastrointestinal, neurological, urinary/genital |

|

|

Bloating |

Gastrointestinal, neurological, urinary/genital |

|

All body systems (even musculoskeletal) |

|

|

Regurgitation |

Gastrointestinal, neurological |

|

Dysphagia (swallowing difficulties) |

Gastrointestinal, neurological |

| From: Tielemans et al, 2013 | |

This article discusses the current

To view the rest of this content please log in

Assessment

As with any assessment in healthcare, the assessment of a patient presenting with symptoms that could be related to the bowels must start with a general examination and history taking (Bickley et al, 2020).

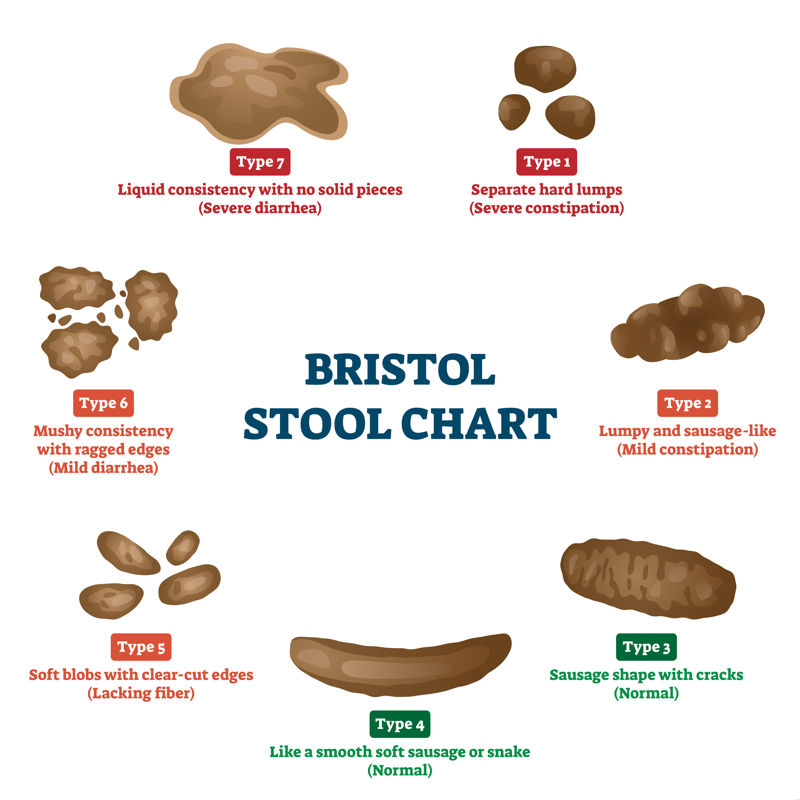

There are simple assessments that can be done before the patient is physically seen at the GP (Crisford, 2016). For example, a verbal assessment of bowel function using the Bristol stool chart (Figure 1) and other bowel disease scores, such as the Harvey Bradshaw Index used in Crohn's Disease (Harvey, 2023), can be used to understand a patient’s symptoms.

To view the rest of this content please log in

Risks and complications

While physical examination in a healthcare setting poses minimal risk, there are factors to consider when undertaking a physical examination. For example, the temperature of the environment should be pleasant, not to hot or cold, and the privacy and dignity of the patient should be a priority (Bickley et al, 2020).

The health professional must gain consent from the patient for the examination and inform the patient that chaperones can be present if wanted. It is important to document these conversations and build a therapeutic relationship with patients by setting out the agenda at the start of a consultation (Fine, 2005; Mocciaro et al, 2014). Remember to familiarise yourself with the emergency equipment in the area you are working in, and how to alert for help in the event of an emergency (Resuscitation Council UK, 2021).

To view the rest of this content please log in

Equipment

- Gloves

- Stethoscope

- Lubricant

To view the rest of this content please log in

Procedure

General examination

When a patient enters a room, or when the nurse approaches the patient, immediate observations can be made. Look for alertness, any alterations in gait, slurring of speech and whether they are looking after themselves (eg if the patient smells) (Bickley et al, 2020). Questions regarding the health of the individual can be answered by simply examining the person’s hands. Clubbing, an enlargement of the ends of the fingers with a downward sloping of the nails (Figure 2), could indicate chronic inflammatory conditions, such as coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease or inflammation of the lungs or heart. Koilonychia or spooning of the nails can indicate an iron deficiency (Potter, 2023). A flapping tremor, signs of inflammation to the person’s skin and other external manifestations of liver disease, should all be looked for and noted, as this can indicate advanced stages of liver disease (Weber, 2008).

To view the rest of this content please log in

Evaluation

A thorough assessment of the bowel should take into consideration the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system and the surrounding organs (Ferguson, 1990; Weber, 2008; Bickley et al, 2020). The peritoneal cavity contains multiple organs, so dysfunction or disease of one can impact directly on other, adjacent organs (Thomas and Monaghan, 2014). For example, abdominal pain can relate to many body systems (Table 1).

With this in mind, it is important to consider some common differential diagnoses in order to decide the next steps, follow-up treatment and additional investigations that may be required. An examination of the respiratory, cardiac system, lymphatic system and a neurological examination should then be considered and carried out if required. Additionally, an advanced nurse should have the knowledge and skills to support a full physical examination if required (Rhoads and Jensen, 2014; Potter, 2023).

To view the rest of this content please log in

NMC proficiencies

Nursing and Midwifery Council: standards of proficiency for registered nurses

Part 1: Procedures for assessing people’s needs for person-centred care

1. Use evidence-based, best practice approaches to take a history, observe, recognise and accurately assess people of all ages

Part 2: Procedures for the planning, provision and management of person-centred nursing care

3. Use evidence-based, best practice approaches for meeting needs for care and support with rest, sleep, comfort and the maintenance of dignity, accurately assessing the person’s capacity for independence and self-care and initiating appropriate interventions

6. Use evidence-based, best practice approaches for meeting needs for care and support with bladder and bowel health, accurately assessing the person’s capacity for independence and self-care and initiating appropriate interventions

To view the rest of this content please log in

Resources

Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG, Hoffman RM et al. Bates' pocket guide to physical examination and history taking. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020

Crisford M. Nurse-led telephone triage for people with suspected colorectal cancer. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2016;15(1):18-25. https://doi.org/10.7748/cnp.15.1.18.s20

Ferguson CM. Inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion of the abdomen. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (eds). Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations. 3rd edn. Butterworths; Boston: 1990

Fine M. The Inner Consultation – how to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style (2e). Health Expect. 2005;8(4):362–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00349.x

GP Notebook. Palpation of the bladder. 2018. https://gpnotebook.com/en-gb/simplepage.cfm?ID=2013659138 (accessed 6 December 2023)

Grover CA, Sternbach G. Charles McBurney: McBurney's point. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(5), 578-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.039

Harvey RF. Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) for Crohn's disease. 2023. https://www.mdcalc.com/harvey-bradshaw-index-hbi-crohns-disease (accessed 6 December 2023)

Knowles SR, Alex G. Medication adherence across the life span in inflammatory bowel disease: implications and recommendations for nurses and other health providers. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2020;43(1):76-88.

To view the rest of this content please log in